Vintage moto heaven in Carmel

If you’re a fan of vintage motorcycles, and guess you are if you’re here…you really need to know about Moto Talbott Museum. Located in Carmel Valley, California, Moto Talbott Museum features more than 170 iconic motorcycles from 16 countries, and is located on one of Northern California’s most beautiful motorcycle roads. The landscape and riding alone is worth the trip there, but once you’re inside, it’s a moto mecca. Founded by Robb Talbott – perhaps best known as the founder of the world-famous Talbott Vineyards and curated curator and restorer by Bobby Weindorf (more on him below). And while Robb Talbott loved his California wines, there was something else equally special to him: motorcycles.

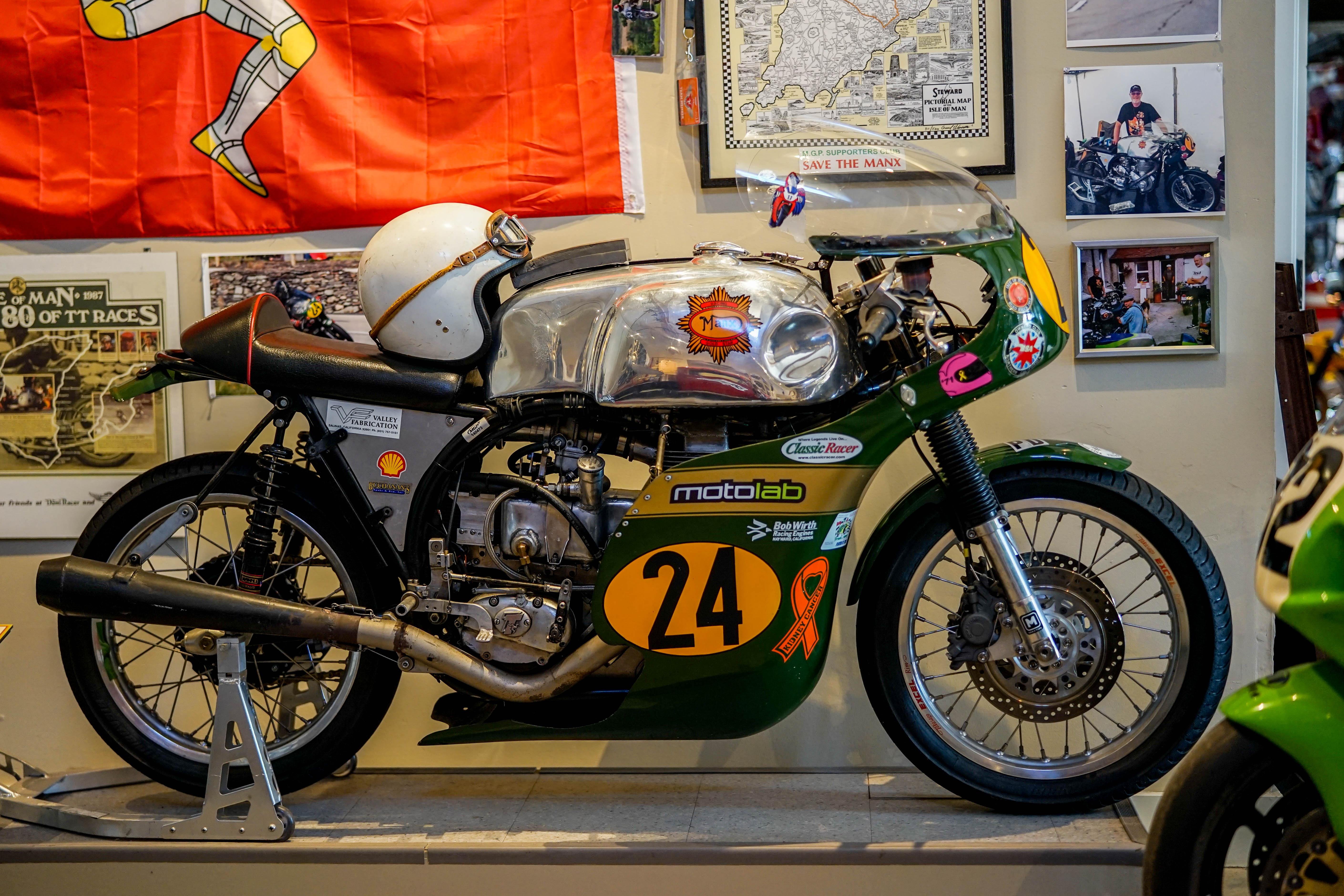

A proper Manx Isle of Man racer

Young Robb developed a youthful fascination with the speed, noise and commotion of the nearby Laguna Seca Raceway. Eventually he acquired a “very used” Honda 50 step-through, which he remembers as “the most fun he’d ever had.” By the time he left to study Fine Art and Design at Colorado College in 1966, Talbott was irretrievably in love with two wheels. He acquired a succession of small displacement Suzukis, and then a pantheon of iconic dirt bikes, including a BSA 441, Jawa, Bridgestone, Kawasaki and a Sachs. But his most memorable bike of all was the venerable two-stroke Yamaha DT-1 250. During this time he raced motocross and winter hill climbs. In 2001, seeking release from the pressures of a demanding work life, he was inspired to buy one of the new, reincarnated Triumph Bonnevilles.

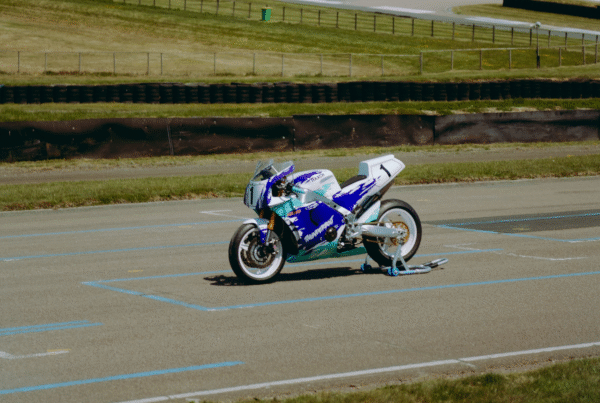

Wayne Rainey’s Yamaha YZR500

500cc’s of 2-stroke goodness

“I never lost my love of motorcycles. This whole thing wouldn’t work if I didn’t have the passion. I love motorcycles.”

— Robb Talbott

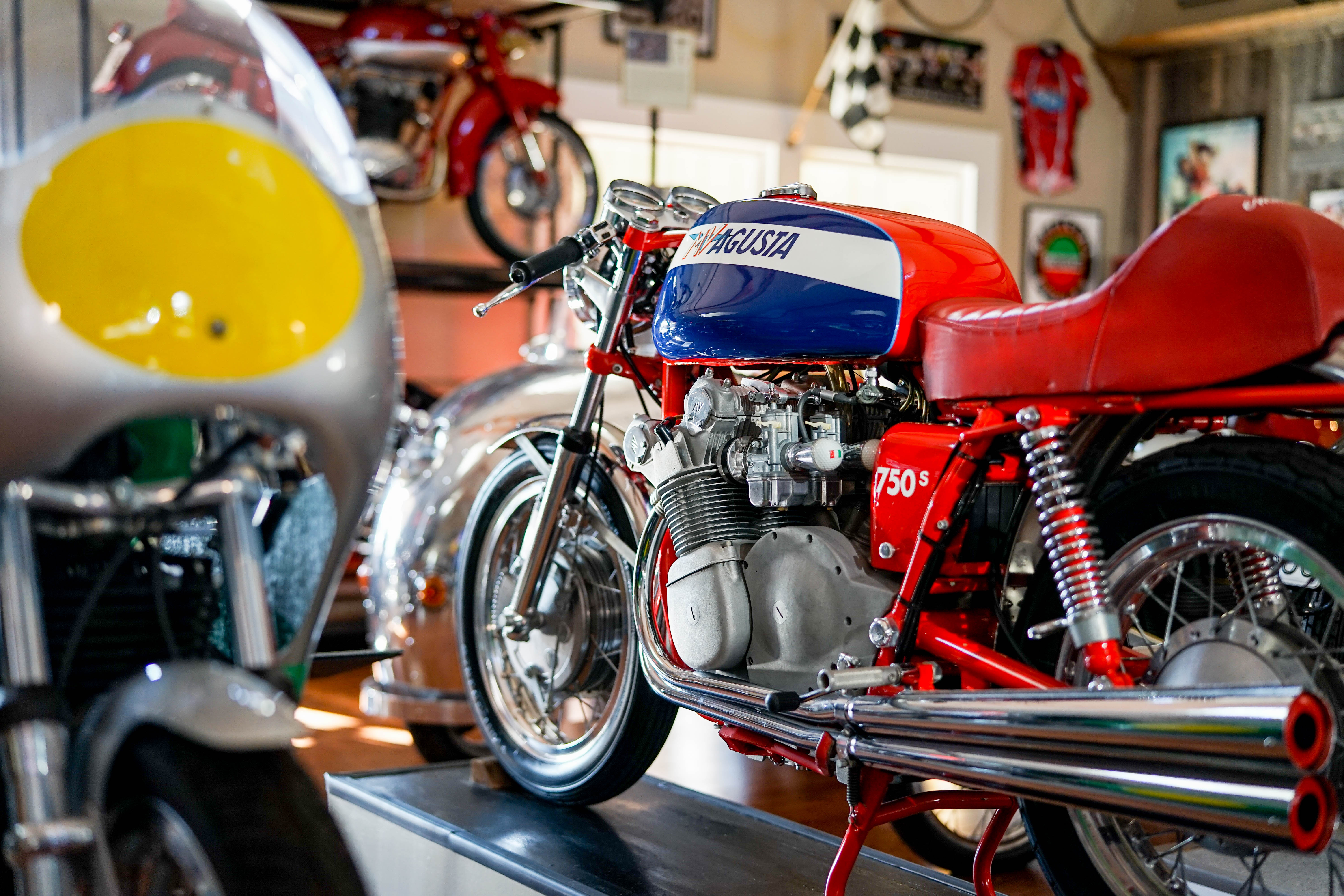

1973 Ducati 750 Sport

Robb read “The Art of the Motorcycle” from the Guggenheim Museum. For Talbott the exhibit was an epiphany: there, framed against the magnificent building, he saw history’s most significant bikes in an artistic context. “For the first time, I realized that motorcycles could qualify as art,” he says. “I started getting really excited about that idea. When you see the cooling fins on an MV Agusta, or the sculpting of a Rickman hub, you realize they’re art.”

Kenny Robert’s 1980 Yamaha YZR500

A lovely MV Agusta 750 Sport

1977 MV Agusta 850SS

Suddenly, Robb found himself buying bikes, for the sheer pleasure of their aesthetic presence. Some he had restored, and others he left as they were, resplendent with the patina of age and their strong pedigree. “I’ve always loved barn bikes,” Robb says. Pretty soon, the barn was full. And before long, the fledgling notion of a museum was born. In 2015, after 33 years of hard work, he sold Talbott Vineyards, and began devoting all his time to the concept of the Moto Talbott Collection, a 501 (c)(3) non-profit devoted to preservation, restoration, and education. By then he had already accumulated more than 140 bikes from 12 countries.

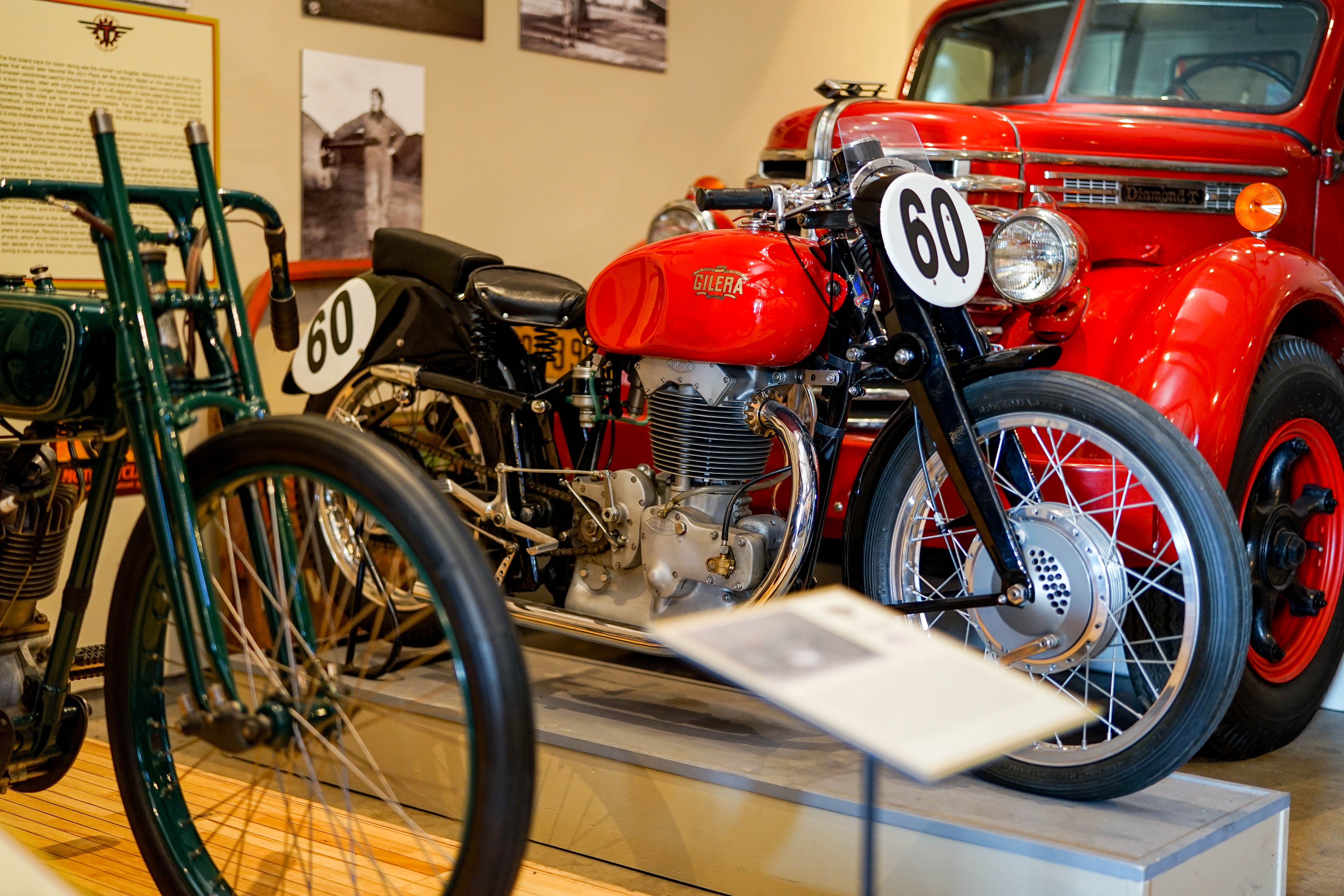

Clearly Robb has eclectic taste

There is no logic to the Talbott collection, other than the most logical thing of all: it’s full of stuff Robb likes. This means three large categories: vintage dirt bikes, MV Agustas and all things Italian; and tiny, 175cc, pre-1957 Motogiro bikes. There are even a few vintage bicycles.

“I don’t believe you can build anything of note without passion,” says Robb. “The motorcycle museum is phase three for me, after the clothing company and the winery. I want to give back to the sport that has given so much to me.

Italian beauty. An old Gilera racer

1911 Indian Board Tracker

1922 Harley Davidson JD Board Racer

Robb Talbott (left), Bobby Weindorf (right)

An Interview with Bobby Weindorf

Imagine if your fulltime job was fettling more than 150 of the world’s most beautiful motorcycles. Welcome to the world of Bobby Weindorf, former factory race mechanic, motorcycle dealer, and ace restorer. Taking care of the prestigious Moto Talbott Museum collection is his fulltime job. We asked him what it’s like.

Q: Do all these motorcycles run?

Weindorf: Yes. I can get anything in here running in 20 minutes or so. There is one bike from China that’s seized, and the Steve McQueen bike is missing a cable and throttle. But it’s my job to make sure all these bikes run!

Q: What are your primary responsibilities at Moto Talbott Museum?

Weindorf: I keep all the bikes running and prep them for shows. And I need to make them correct. When Robb finds a new project, we need to make a decision: should I just make it run? Should I do a cosmetic restoration, or a full mechanical restoration? That depends on how far gone the bike is. And some bikes are left in their original state, to better convey their history and provenance.

We get some bikes that have hokey parts, or are missing things. So I do a lot of research, and get a lot of parts from Italy, Spain, and BMW. With BMW, I spend a lot of time contacting their archive to make sure things are correct.

Q: How did you meet Robb?

Weindorf: Robb came down to southern California to visit another collector I’ve worked for, Guy Webster. Robb said he had an old Husky he wanted restored, and I told him I’d do it. I came up to Carmel, restored that bike. Then he wanted a Vespa restored, and I did that. Then he said he wanted to start a museum, and did I want to move north? So I did.

Q: What are the most typical restoration tasks you perform?

Weindorf: I call it the “Ps”: Paint, polishing, powdercoating, and plating. We don’t have a paint booth, and there is no polisher nearby, so we have to send out for those things. And chromers are getting harder and harder to find. The best chromer in the country, in Kentucky, just closed. I try not to have very many parts powdercoated, but it can be the right choice for the frame and other parts that get banged around a lot.

So often it’s just the little things. Bikes are missing parts, or something small is incorrect. Sometimes I look at a bike with a strange modification or part and think, “What was someone thinking here?”

Q: Do you have to fabricate parts for very old or rare bikes?

Weindorf: Some things will require machining or fabrication, like bronze swingarm bushings. And some bikes have parts that are un-obtain-ium, and you have to figure out how to have them made. If it was a cast part, you’re stuck. Some companies were only in existence for a few years, like the Italian Devil. Where in the hell are you going to find parts for that?

But getting parts has actually gotten easier, thanks to the Internet. Instead of contacting one or two guys that you happen to know, you now have the whole world to look for parts.

Q: Are there problems that are specific to a country or brand?

Weindorf: Every manufacturer is different, and you can definitely see trends among the Germans, the Italians, and the British. But basically, they’re just two wheels and a motor.

Mechanically they’re not too difficult, unless someone blew up the engine. These bikes are pretty bulletproof. The most common thing to fail is wiring. But I love wiring and electrical problems. Old wires fray. Some bikes have specific known issues, like the “slinger” [sludge trap] on old BMWs. If it’s too full, the engine doesn’t get lubrication, and it blows up. So there are things like that, which you know you have to check.

Q: You’ve worked as a mechanic for factory race teams. How does this compare?

Weindorf: Old stuff is good to work on, because it’s so basic. You can get into every part of it—nothing is out of reach. With modern bikes, there are some things that you would never attempt to take apart. Just trying to set valves on modern bike is a headache. With these bikes, if you give me 20 minutes, I’ll have all the valves done. I love the simplicity of old bikes.

New bikes have amazing traction control, and wheelie control, and ABS—but these old bikes in many ways are more enjoyable and accessible. People are intimidated by vintage bikes, but they are really, really easy, once you have a have basic understanding of mechanics and motors. They’re all just variations on a theme. Does it have gas, compression, and a spark? Keeping them running involves checking valves and changing oil. Those are the cheapest insurance measures you can do.

Q: After all these years of wrenching, are you still learning new things?

Weindorf: All these bikes have their special significance and cool factor. We have a BMW R25 with a three-slide carburetor. I thought, “Wow! I’ve never seen that before!” So I took it apart to look at it. It’s wonderful and primitive at the same time.

Q: What do you ride personally?

Weindorf: People like to ask me that! It depends on what day it is. My favorite bikes are whatever is in my garage. There are 30 bikes in there. I just have to decide what I’m doing that day. Some Sundays I’ll ride three different bikes: one to the coffee shop in the morning, another for a lunch ride, and another for a little longer ride. Mostly I rotate between three: my Ducati Multistrada, Moto Guzzi V7, and Honda GB500. I seem to be in a 500 phase. I also have a Triumph 500, a Yamaha RZ500, and a Fiat 500 car. I have a lot of 500 stuff in my life.

I’ve had bigger bikes—my Ducati is big, and I’ve had superbikes, Aprilias, and an MV F4. They’re plenty fast, but I’ll never be able to use all that horsepower on the street. I find the smaller, lighter bikes so much more fun. They give a better illusion of speed. The V7 in the real world is kind of slow and old feeling, but you get the feeling you’re going really fast when you’re doing 50mph! It’s all about how you feel. I could ride my MV and go 140mph—it’s so new and perfect, it doesn’t feel like anything. But you have to be going 140mph! Which is friggin’ crazy….